We discuss lessons from a research study undertaken for the Lancet Citizen’s Commission on Reimagining India’s Health Systems. The study highlights how healthcare came to be seen as a politically viable and electorally rewarding issue in some, but not nearly enough, States.

Author: Nikhil Iyer

Published: August 11, 2022 in The Hindu Business Line

Ask any politician at random if they think healthcare needs to be prioritised in India, and they are likely to say yes. Yet, there seems to be a sense of reluctance in making healthcare a political priority.

As India turns 75, we discuss lessons from a research study undertaken for the Lancet Citizen’s Commission on Reimagining India’s Health Systems. The study highlights how healthcare came to be seen as a politically viable and electorally rewarding issue in some, but not nearly enough, States.

Early 2022, Tamil Nadu and Rajasthan indicated they would legislate a Right to Health for their citizens. An emphatic political expression by the respective Chief Ministers, these bills signify a culture where politicians feel incentivised to deliver better healthcare as their competitors try to one up them.

Take Tamil Nadu’s case. The Right to Health Bill’s antecedents include a maternity benefits scheme for women’s nutritional security (1987), procurement and distribution of free medicines (1994), health insurance (2009), and so on. Over decades, motivated by the Dravidian ideology, leaders like K Karunanidhi, MG Ramachandran and J Jayalalithaa pursued initiatives which have embedded an expectation of health among voters. Present-day politicians, who seek to sustain their legacies, thus have an incentive to continue reforms.

Competitive political issue

In Rajasthan, health has become a thriving, competitive political issue in the past decade. In 2011, then Chief Minister Ashok Gehlot introduced the free medicines and diagnostics schemes, which went on to become so popular even his successor Vasundhara Raje had to continue it, despite murmurs about watering it down. Later in 2013, as CM, Raje introduced a health insurance scheme, and set up ‘Model PHCs’. On returning as CM in 2018, Gehlot first expanded the coverage and eligibility under the insurance scheme, and has now introduced the Right to Health Bill.

There have been few more instances where Chief Ministers decided to bet big on health, in turn affecting voter expectations of other politicians in the State. A relevant example is the legacy of YS Rajasekhara Reddy in Andhra Pradesh, which is claimed by his son Jaganmohan Reddy today. YSR introduced the Rajiv Aarogyashri Scheme, the first State-wide health insurance scheme for families below the poverty line in India, in 2007, seeking to create a pro-welfare, rural-centric image for himself.

The insurance scheme’s ensuing popularity ensured that even when the opposition led by Chandrababu Naidu came to office, they could not roll it back, due to pressure from both citizens as well as hospital associations who benefited from the scheme. Jaganmohan Reddy, as the incumbent CM, has expanded the list of procedures and benefits under the scheme.

These examples indicate a much warranted shift. We can observe a virtuous loop of political action and voter demand — as most apparently has happened in Rajasthan. What started off as a free medicines and diagnostics scheme has today snowballed into a political plank for both major parties in Rajasthan. Good service delivery arguably leads to loss aversion among the voters, which builds pressure on competitor politicians to continue the scheme, and build on it. Even smaller reforms, such as guaranteeing delivery of medicines, may begin to change the political culture, and eventually lay the path for the State to pursue systemic reform.

Healthcare is by no means an easy issue to fix. Even after 75 years, our health system pushes more than 50 million people into poverty each year, with out-of-pocket-expenditure as high as 70 per cent in some States. The Covid-19 pandemic further uncovered the deficiencies of the Indian public health system.

One might expect politicians would have adequate incentives to care for this issue that virtually affects every voter. Yet, there is a marked absence of mainstream political discourse around health financing, outcomes, human resources in health, etc. This must change, and maybe our politicians, inspired by the examples above, will be incentivised to surprise the voters with a new political agenda involving healthcare.

Author: Nikhil Iyer is Senior Public Policy Analyst at The Quantum Hub Consulting

A lot has been written about the proposed amendments to the IT Rules. Many commentators have raised concerns that the rules go beyond the remit of the IT Act and seek more control of content moderation even as challenges are still pending in the courts. There have also been questions about the government setting up Grievance Appellate Committees and whether that will lead to political interference in moderation and censorship of critical voices.

A lot has been written about the proposed amendments to the IT Rules. Many commentators have raised concerns that the rules go beyond the remit of the IT Act and seek more control of content moderation even as challenges are still pending in the courts. There have also been questions about the government setting up Grievance Appellate Committees and whether that will lead to political interference in moderation and censorship of critical voices.

The payments ecosystem in India is in for a stir. Reserve Bank of India’s no-card-storage directive initiated in March 2020 is set to kick-in from July 1st, 2022. Starting July, both authorised payment aggregators and merchants will not be allowed to store customer card credentials. Instead, transactions will have to be processed through a card ‘token’ – an alphanumeric code unique to every combination of card and merchant.

The payments ecosystem in India is in for a stir. Reserve Bank of India’s no-card-storage directive initiated in March 2020 is set to kick-in from July 1st, 2022. Starting July, both authorised payment aggregators and merchants will not be allowed to store customer card credentials. Instead, transactions will have to be processed through a card ‘token’ – an alphanumeric code unique to every combination of card and merchant. The anxiety being caused by this information asymmetry is being further aggravated by the ecosystem’s recent experience with RBI’s e-mandate on recurring payments. A

The anxiety being caused by this information asymmetry is being further aggravated by the ecosystem’s recent experience with RBI’s e-mandate on recurring payments. A

Imagine a 16-year-old boy getting his first smartphone in a tier-3 city. He has attended school online for two years of the pandemic. He helps his parents download and use new apps. His primary means of shopping is online and he orders for the family.

Imagine a 16-year-old boy getting his first smartphone in a tier-3 city. He has attended school online for two years of the pandemic. He helps his parents download and use new apps. His primary means of shopping is online and he orders for the family.

Try recalling the last time you earnestly read through a verbose and jargon-laden privacy policy before consenting to share your data – but don’t beat yourself over being lax about it. Multiple studies have demonstrated that privacy policies and informed consent are broken. They suffer from three behaviourally-linked problems. First, the transparency/ comprehension problem – wherein the verbose legalese used in privacy policies is often incomprehensible to laypeople; this problem is further compounded by low digital literacy in India. Second, the data repurposing problem – where entities do not overtly disclose all the additional purposes for which user data could be used, thereby resulting in ‘function creeps’. And third, the consent fatigue problem – where users, by virtue of having to repeatedly consent to data sharing, are tired of doing so, thereby unwilling to expend the time and effort required to meaningfully consent.

Try recalling the last time you earnestly read through a verbose and jargon-laden privacy policy before consenting to share your data – but don’t beat yourself over being lax about it. Multiple studies have demonstrated that privacy policies and informed consent are broken. They suffer from three behaviourally-linked problems. First, the transparency/ comprehension problem – wherein the verbose legalese used in privacy policies is often incomprehensible to laypeople; this problem is further compounded by low digital literacy in India. Second, the data repurposing problem – where entities do not overtly disclose all the additional purposes for which user data could be used, thereby resulting in ‘function creeps’. And third, the consent fatigue problem – where users, by virtue of having to repeatedly consent to data sharing, are tired of doing so, thereby unwilling to expend the time and effort required to meaningfully consent.

As of 2021, India had issued over 1.31 billion digital identity cards via its Aadhaar platform, and over 1.1 billion digital vaccine certificates via its CoWin platform. More recently, its Unified Payments Interface (UPI), crossed the $1-trillion mark in transaction values after it recorded 5 billion transactions in a month for the first time in March 2022.

As of 2021, India had issued over 1.31 billion digital identity cards via its Aadhaar platform, and over 1.1 billion digital vaccine certificates via its CoWin platform. More recently, its Unified Payments Interface (UPI), crossed the $1-trillion mark in transaction values after it recorded 5 billion transactions in a month for the first time in March 2022. Second, India’s strong political will and deliberative policy making – has been crucial in providing high-level direction to steer ecosystem efforts. For instance, Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology’s decisions to incentivize the use of open technology, through Policy on Adoption of Open Source Software, Policy on Open APIs, Policy for Open Standards etc., has expedited the creation of digital public infrastructure and digital public goods. An example of the benefits of such technology is the use of open APIs to leverage the Aadhaar database for providing services like eKYC, DigiSign etc.

Second, India’s strong political will and deliberative policy making – has been crucial in providing high-level direction to steer ecosystem efforts. For instance, Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology’s decisions to incentivize the use of open technology, through Policy on Adoption of Open Source Software, Policy on Open APIs, Policy for Open Standards etc., has expedited the creation of digital public infrastructure and digital public goods. An example of the benefits of such technology is the use of open APIs to leverage the Aadhaar database for providing services like eKYC, DigiSign etc.

The Justice Sri Krishna Committee Report on a Free and Fair Digital Economy, which was the basis for the Personal Data Protection Bill, was released in July 2018. Until then, India had 16 unicorns – startups with a valuation of US$ 1 billion or more. Since then, there have been 84 more unicorns (as of May 2022). The upcoming law on data protection, currently under deliberation by the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology, must create a conducive growth environment so that India’s startup ecosystem keeps thriving.

The Justice Sri Krishna Committee Report on a Free and Fair Digital Economy, which was the basis for the Personal Data Protection Bill, was released in July 2018. Until then, India had 16 unicorns – startups with a valuation of US$ 1 billion or more. Since then, there have been 84 more unicorns (as of May 2022). The upcoming law on data protection, currently under deliberation by the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology, must create a conducive growth environment so that India’s startup ecosystem keeps thriving.

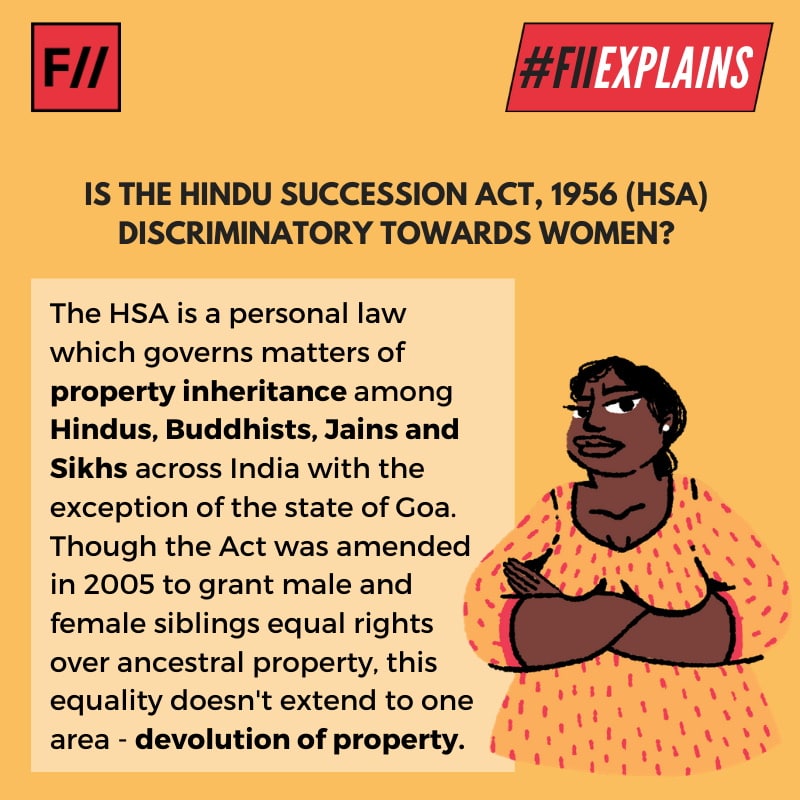

Imagine a married couple without any children. The husband and wife work their whole lives, build their property and stash away savings in a joint bank account – hoping it will help in taking care of their ageing parents. Yet, when they die suddenly, without a will, all of their movable and immovable property is transferred to the husband’s parents. The wife, although economically independent and empowered, fails to provide for her parents because the 1956 Hindu Succession Act (HSA) which applies to 80% of India’s population including Buddhists, Sikhs, and Jains, dictates different schemes of property devolution for men and women if they do not have a surviving spouse or children: All of the husband’s property goes to his natal family, but the women’s property devolves to her in-laws.

Imagine a married couple without any children. The husband and wife work their whole lives, build their property and stash away savings in a joint bank account – hoping it will help in taking care of their ageing parents. Yet, when they die suddenly, without a will, all of their movable and immovable property is transferred to the husband’s parents. The wife, although economically independent and empowered, fails to provide for her parents because the 1956 Hindu Succession Act (HSA) which applies to 80% of India’s population including Buddhists, Sikhs, and Jains, dictates different schemes of property devolution for men and women if they do not have a surviving spouse or children: All of the husband’s property goes to his natal family, but the women’s property devolves to her in-laws.

A year into the pandemic, its devastating impacts have disrupted social and economic infrastructure and have further marginalized millions of people. In many ways, the epicentre of the pandemic was felt among the urban informal workers in the country, particularly women. Already existing at the edge of precarity with respect to livelihood, social security, and shelter – all of which lay on the spectrum of informality – the humanitarian crisis brought about by the pandemic further widened the fault lines of their pre-existing social and economic vulnerabilities. As the government urged people to stay at home and the economic cogwheels of the country came to a grinding halt, India witnessed one of the worst recessions since independence, with the economy shrinking by a historic 7.3% in the first year of COVID. Overnight, urban informal workers across the country lost their jobs and incomes.

A year into the pandemic, its devastating impacts have disrupted social and economic infrastructure and have further marginalized millions of people. In many ways, the epicentre of the pandemic was felt among the urban informal workers in the country, particularly women. Already existing at the edge of precarity with respect to livelihood, social security, and shelter – all of which lay on the spectrum of informality – the humanitarian crisis brought about by the pandemic further widened the fault lines of their pre-existing social and economic vulnerabilities. As the government urged people to stay at home and the economic cogwheels of the country came to a grinding halt, India witnessed one of the worst recessions since independence, with the economy shrinking by a historic 7.3% in the first year of COVID. Overnight, urban informal workers across the country lost their jobs and incomes. While several studies have been conducted on how workers can be best supported during such periods, there are gaps in existing data and research around the subject of women informal workers. This study hopes to fill those gaps and bridge the distance between research on pre-pandemic vulnerabilities, and institutional policy responses through the course of COVID-19 by looking at such workers in the context of the Delhi National Capital Region (NCR). In the absence of clear policy safeguards, the report also delves into informal channels and actors that organized during the pandemic and how similar such interventions can be supported.

While several studies have been conducted on how workers can be best supported during such periods, there are gaps in existing data and research around the subject of women informal workers. This study hopes to fill those gaps and bridge the distance between research on pre-pandemic vulnerabilities, and institutional policy responses through the course of COVID-19 by looking at such workers in the context of the Delhi National Capital Region (NCR). In the absence of clear policy safeguards, the report also delves into informal channels and actors that organized during the pandemic and how similar such interventions can be supported.