Authors: Rohit Kumar & Paavi Kulshreshth

Published: 20th May, 2025 in The Indian Express

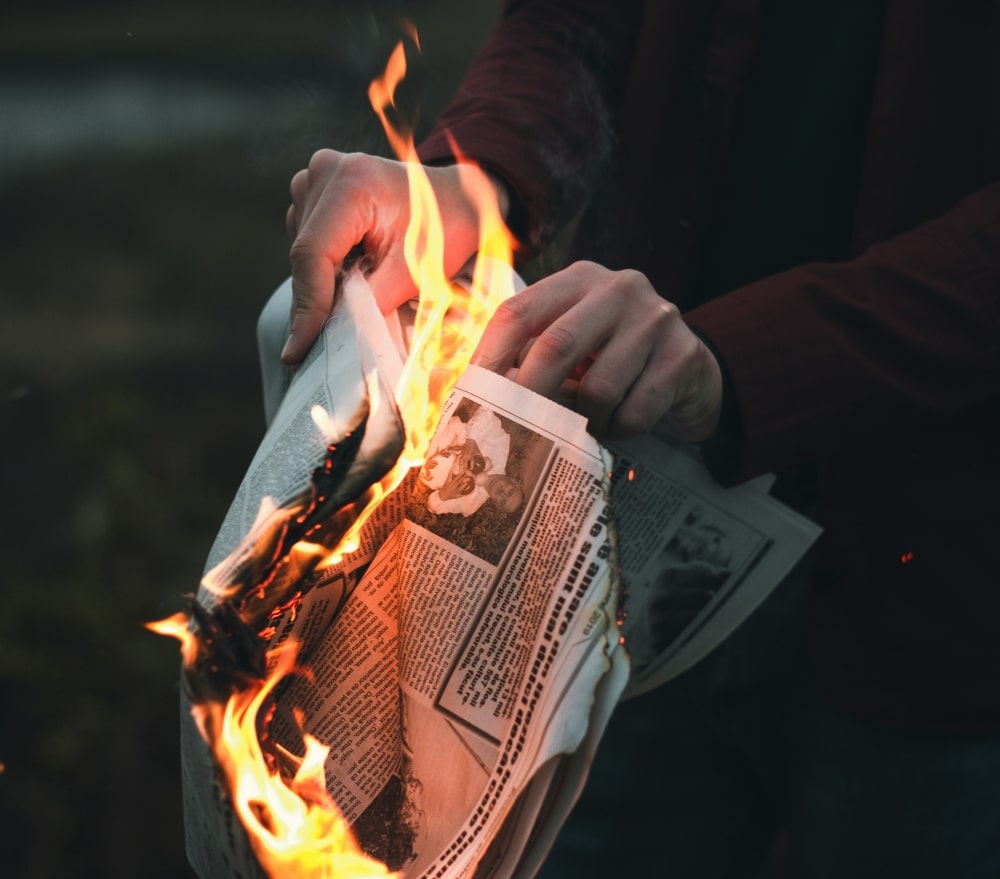

India’s military strength was on display in the recent conflict with Pakistan, where the Air Force responded with precision and resolve. But even as our forces have returned to base, a parallel battle has continued to rage online: one of narratives, falsehoods, and influence. This front – digital and unrelenting – requires not just speed, but strategy since conventional tools of control offer little defence against the evolving nature of information warfare.

Amid the conflict, reports flagged a surge in disinformation from pro-Pakistan social media handles, including absurd claims such as India attacking its own city of Amritsar. This pointed to deliberate, coordinated efforts to systematically weaponise disinformation on digital platforms. In response, India was quick to hold press conferences, present visual evidence, and have the PIB fact-checking unit debunk false claims, while also issuing an unprecedented number of account blocking orders. All of this put together, however, was not enough to prevent falsehoods from gaining traction.

Disinformation is not a new phenomenon – it has long been used as a tool in warfare and diplomacy. What’s changed is the scale, speed, and precision with which it now spreads through digital platforms, transforming old tactics into persistent and formidable threats. Around the world, policymakers have struggled to keep pace. In India, one of the recurring proposals has been to weaken safe harbour protections for online platforms. But this is a misdiagnosis of the problem – and a potentially counterproductive one.

Why Safe Harbour Isn’t the Problem

Today’s disinformation is not just about individual false posts; it is about coordinated influence operations that weaponise platform features to shape public perception at scale. Blocking a few posts or suspending some accounts is unlikely to stop narratives from being replicated and recirculated across the digital ecosystem. Nor does it disrupt the underlying dynamics – like trending algorithms or recommendation engines – that give such content disproportionate visibility.

In this context, calls to dilute safe harbour reflect a fundamental misunderstanding. Safe harbour, as it currently operates, holds platforms liable only if they have actual knowledge of illegal material and choose to keep it up. This framework exists because requiring platforms to pre-screen every post is not just technically infeasible given the sheer volume, but would also lead to over-censorship and weakening of the digital public sphere.

Crucially, much of the disinformation we see during geopolitical conflicts is not technically illegal. For instance, when a Chinese daily reportedly shared false information on X amid the India-Pak conflict, X’s legal obligation wasn’t clear, as the content wasn’t technically illegal. This would remain unchanged even if safe harbour is weakened.

Blunt instruments like safe harbour dilution are therefore unlikely to be effective against systemic challenges such as disinformation.

Shift from reactive content moderation to systemic resilience

To effectively counter disinformation, we must shift from reactive content moderation to a systems-level approach rooted in platform accountability and design resilience. This means recognising that disinformation thrives not only because of bad actors, but because of how platforms are built. Regulatory and platform responses must therefore focus on preventing exploitation of platform features, rather than merely responding to viral falsehoods.

A key step toward prevention is mandating periodic risk assessments for platforms that host user-generated content and interactions. These assessments should identify which design features – such as algorithmic amplification or low-friction-high-reach sharing – contribute to the spread of disinformation. Platforms should then be required to arrive at solutions and strengthen internal systems to slow the speed and breadth of spread of disinformation.

This approach matters because platform architecture directly influences how disinformation spreads. Bad actors exploit different services in different ways – gaming open feed algorithms to promote manipulative content on one platform, while leveraging mass forwards and group messaging on another. Risk assessments must capture these distinctions to inform tailored, service-specific mitigation strategies.

On public platforms, safety-by-design measures can include fact-checking nudges, community notes, content labelling (especially for AI-generated content). In encrypted messaging environments, where direct moderation is not possible, design interventions such as limiting group sizes, restricting one-click forwards, or introducing forwarding delays can reduce virality without compromising user privacy.

Equally important is the ability to detect and attribute coordinated disinformation activity – campaigns orchestrated by networks of actors often disguised as ordinary users. Addressing this requires both platforms and regulators to invest in tools and intelligence capabilities that go beyond flagging individual posts. Network analysis and behaviour-based detection systems can help identify the source and structure of such campaigns, rather than focusing only on visible front actors.

When platforms fail to act despite foreseeable risks, remedies should target specific penalties, calibrated to the severity and impact of the violation. This approach targets platform responsibility for system design and risk management – not for individual pieces of user content, and thus remains separate from content-level liability under safe harbour.

A Future-Ready Approach

While disinformation is especially dangerous during sensitive geopolitical moments, it festers even in peacetime, distorting everything from health to gender politics. The rapid evolution of technology, especially the rise of AI-generated content, is further blurring the line between fact and fiction. Regulation must start with a clear-eyed understanding of these dynamics – because if we misdiagnose the problem, we’ll keep fighting the wrong battle.

Rohit Kumar is the founding partner, and Paavi Kulshreshth a senior analyst at the public policy firm The Quantum Hub (TQH)